Her face still haunts me five years later. I can still see the image of her crystal-encrusted skull with the jaw open, frozen in a silent scream. The rest of the skeleton was perfectly preserved in stone, arms askew above her head and legs spread apart. The preservation was so complete that you could make out the individual bones of the fingers. Above her head lay a beautifully carved jade axe. Was it used in her murder? |

|||

|

|||

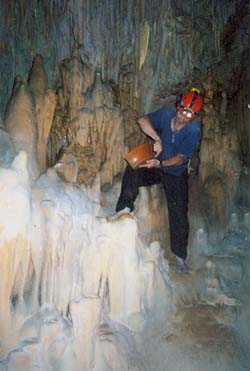

Actun Tunichil Muknal was a major ceremonial site to the Maya.

Mapping, documenting, and preserving the remains in the cave has

been an on-going process by archaeologists for the last 6 years.

The cave was named for the stone altar discovered over ½

mile into the cave. On a ledge forty feet above the underground

river, an altar was constructed over 1000 years ago. Two slate

stelae or monuments were placed upright within a grouping of broken-off

cave formations. The four foot long stelae represented objects

used in the bloodletting rituals, obsidian blades and stingray

spines. In ancient Mayan times, the high priest would puncture

a body part and let the blood drip onto a piece of bark inside

a bowl. The bark would then be burned so that the smoke would

rise to the heavens as homage to the gods. The objects of this

ceremony were found scattered around the altar, obsidian blades,

elaborately decorated bowls, and faces carved into slate slabs. |

|||

|

|

In

the far reaches of the chamber, you climb vertically twenty

feet up to an alcove. It is here that you gaze upon the girl's

skeleton. You can't help but be mystified by the sight. Everyone

quietly leaves the chamber, wondering what happened at this

site a thousand years ago.

Actun

Tunichil Muknal is now open to the adventurous public. This

wondrous underground archaeological site is now a living museum.

The human remains and artefacts would not have as much importance

if removed to a display cabinet. By seeing these objects in

their original context, the ecotourist can appreciate what it

meant to the ancient Maya. All photos provided by Dr. Bruce Minkin. All rights reserved. |