|

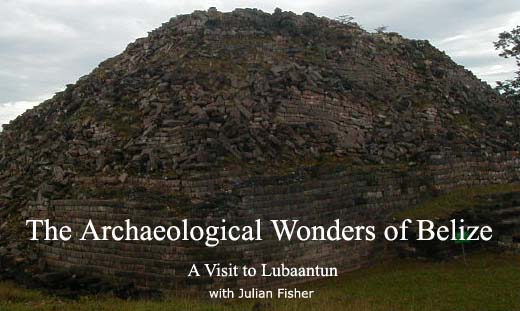

Translated "Place of the Fallen Stones" Lubaantun, about twenty-six miles northwest of Punta Gorda, two miles from the village of San Pedro Columbia is one of the least visited major Maya. The

city dates from the Maya Classic era, flourishing from the 730s

to the 890s, and seems to have been completely abandoned soon

after. The architecture is somewhat unusual from typical Classical

central lowlands Maya sites. Lubaantun's structures are mostly

built of large stone blocks laid with no mortar. Several structures

have distinctive "in-and-out masonry"; each tier is

built with a batter, every second course projecting slightly beyond

the course below it. Corners of the step-pyramids are usually

rounded, and lack stone structures atop the pyramids; presumably

some had structures of perishable materials in ancient times. |

||||||

The centre of the site is on a large artificially raised platform between two small rivers; it has often been noted that the situation is well suited to military defence. At the start of the 20th century inhabitants of various Kekchi and Mopan Maya villages in the area mentioned the large ruins to inhabitants of Punta Gorda. Dr. Thomas Gann came to investigate the site in 1903, and published two reports about the ruins in 1905.

The next expedition was led by R. E. Merwin of Harvard University's

Peabody Museum in 1915 who cleared the site of vegetation, made

a more detailed map, took measurements and photographs, and made

minor excavations. Of note Merwin discovered one of the site's

three courts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame, which had

stone markers with hieroglyphic texts and depictions of the ballgame. |

||||||

In 1924 Gann revisited the ruins, and then led adventurer F.A. Mitchell-Hedges to the site. In his typically sensationalistic fashion, Mitchell-Hedges published an article in the Illustrated London News claiming to have "discovered" the site. Gann made a new map of the site. The following year Mitchell-Hedges returned to Lubaantun with his companion Lady Richmond Brown and his daughter Anna, and conducted some minor excavations. Mitchell-Hedges wrote that the famous crystal skull was found here at this time, although some archaeologists strongly suspect that Mitchell-Hedges either planted the skull for his daughter to find on her birthday or simply fabricated the whole story of finding it at Lubaantun. Uncharacteristically the publicity-loving Mitchell-Hedges did not even publish any mention of the skull until the late 1940s. The magazine Fate even ran an investigation that concluded that the skull was not found at Lubaantun at all, but was bid off at a Sotheby's in the 1940s. The British Museum sponsored investigations and excavations at Lubaantun under T.A. Joyce in 1926 and 1927, establishing the mid to late Classic period chronology of the site. After this Lubaantun was neglected by archaeologists (although it suffered some looting by treasure hunters) until 1970, when a joint British Museum, Harvard, and Cambridge University project was begun led by archaeologist Normand Hammond. Thanks to Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, for their assistance. |

||